The growth of e-commerce continues to wreak havoc on traditional retail and its workforce, with 5,300 store closings announced in the first half of 2017 and 64,000 job cuts expected. What will become of the 16 million Americans who work in the retail industry as current trends toward online shopping continue? Economics correspondent Paul Solman reports.

HARI SREENIVASAN: But first: As more and more shopping is done online, what will become of the 16 million Americans who work in the retail industry?

Our economics correspondent, Paul Solman, takes a look. It’s part of our series Making Sense, which airs Thursdays on the NewsHour.

JENNIFER RICHTER, Former Regional Director, Macy’s: This is a great, great, great basic black top.

PAUL SOLMAN: This summer, Jennifer Richter opened her own clothing boutique online.

JENNIFER RICHTER: This is just the future of retail. The brick-and-mortar stores, they’re just going to keep trimming the fat and keep eliminating positions.

PAUL SOLMAN: Richter speaks from experience. In January, she was one of over 10,000 employees laid off from struggling department store chain Macy’s.

JENNIFER RICHTER: It just spiraled out of control with traffic down, people not coming in, online sales going up. And it just happened really fast.

PAUL SOLMAN: Richter worked at Macy’s in Manhattan as one of 14 regional directors for stylists. Every one of her colleagues was axed.

So, far as you know, 12 out of 14 still looking for work half-a-year later?

JENNIFER RICHTER: Yes.

And I was with Macy’s for two years, and the other 12 are 10 years-plus. Some of them had been with the company for 30 years. And when you get to the level we were at, it’s harder and harder. It’s scary. It really is.

PAUL SOLMAN: Unable to find work at another retailer, Richter is going it alone.

JENNIFER RICHTER: Really just using Instagram, social media to really market myself, and instead of fighting online, like I did for so many years, I’m just embracing it and joining them in doing what I feel there’s a need in the market for.

PAUL SOLMAN: As you have surely heard by now, the growth of e-commerce is wreaking havoc on traditional retail and its work force; 5,300 store closings were announced in the first half of 2017, empty storefronts you have probably seen somewhere near you.

More painful, the 64,000 job cuts said to be in the works.

Mark Cohen runs the retail studies program at Columbia Business School.

MARK COHEN, Columbia Business School: The retail worker is in a world of hurt. Retail employees, some 10 percent of the employed population of the United States, these are folks who are often tethered by way of employment to a shopping mall.

There’s no pathway from a part-time job in a mall, in a specialty store or department store to some other form of employment that’s local and available.

PAUL SOLMAN: Official statistics show the retail sector shedding only 26,000 or so jobs in the past 12 months, but Cohen says that may understate the case.

MARK COHEN: I think it’s going to be difficult to pinpoint the employment status of the folks being laid off. Many of them are part-time employees, so they don’t necessarily get captured in the employment numbers.

PAUL SOLMAN: Malcolm Skoop Hovis worked at old-time retailer Kmart.

MALCOLM SKOOP HOVIS, Retail Worker: Kmart got to compete with Wal-Mart, Target, Walgreens, with Amazon doing deliveries now, so it’s too much competition for Kmart.

PAUL SOLMAN: Hovis was hired as a temp at this Kmart outside Washington months before it closed.

MALCOLM SKOOP HOVIS: Half the store is empty. The inventory is getting smaller. And you can come in here and get little knickknacks.

PAUL SOLMAN: More than 300 Sears and Kmart stores are scheduled to close this year. Sears Holding Company, which also owns both Sears and Kmart, has shed some 180,000 jobs in the last seven years.

Mark Cohen was once a Sears executive.

MARK COHEN: I spent seven years at Sears, both here in the United States and in Canada. They are hanging on by a fingernail, at best. The genre that was legacy retail is, for the most part, in terrible trouble.

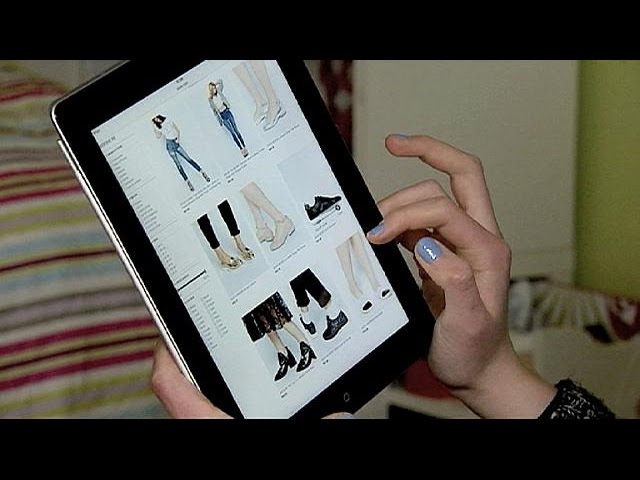

PAUL SOLMAN: The main reason will not surprise you. One-eighth of all retail sales were transacted online last year, up 16 percent over just the year before, more folks shopping on computers and phones, fewer driving to the malls, some of which have literally gone to seed.

There’s another threat to retail jobs as well, automation, as in cashier-less convenience stores, like those being tested in China and closer to home.

So, toll the knell for jobs in retail? Not just yet.

MICHAEL MANDEL, Progressive Policy Institute: Since 2007, we have seen about 400,000 jobs created in the e-commerce sector.

PAUL SOLMAN: Michael Mandel, chief economic strategist at the Progressive Policy Institute, thinks online may spawn more jobs than it whacks.

MICHAEL MANDEL: We have had a small decline in brick-and-mortar retail. We have had a large increase in e-commerce jobs. A lot of them are jobs in fulfillment centers.

PAUL SOLMAN: Mandel argues that much of the growth in warehouse employment is actually tied to online retail.

MICHAEL MANDEL: I have been able to track these jobs using government data down to the county level. And you can see, when a fulfillment center opens up in the county, you have a big jump in what the government classifies as warehouse jobs.

PAUL SOLMAN: On a recent morning in hot summer Baltimore, thousands of job-seekers lined up outside an Amazon fulfillment center for a one-day jobs fair held at a dozen sites across the country to recruit 50,000 workers to pick, pack, and ship orders.

PAUL SOLMAN: Amazon’s Lauren Lynch:

LAUREN LYNCH, Amazon Spokesperson: Here in Baltimore, we’re looking to fill 1,200 roles.

A few years ago, we didn’t have 70 fulfillment centers across the country. Now we have got more than 70, and we need associates to help us fill those orders.

PAUL SOLMAN: OK, maybe every retailer now calls its employees associates these days.

But no matter what they do, more than 382,000 employees work for Amazon worldwide, and the number is growing. In January, the company promised to create 100,000 more jobs in the U.S. alone.

CANDACE TAYLOR, Amazon Job Applicant: I think Amazon’s going to rule the world soon.

(LAUGHTER)

PAUL SOLMAN: Single mom Candace Taylor got a job offer after almost a year of unemployment.

CANDACE TAYLOR: I’m a little older, and for me to have a company that’s stable and to have something that can become a career is exactly what I need.

PAUL SOLMAN: Also, the above-minimum-wage pay and benefits, health insurance, retirement, are better than at the mall.

DAMION BROWN, Amazon Job Applicant: They say they’re starting off at $13 an hour.

PAUL SOLMAN: Damion Brown makes $10 an hour at Wal-Mart.

DAMION BROWN: Wal-Mart, it’s OK. It’s not — I wouldn’t say it’s the best. You’re not getting the pay, right? You might get the hours. You are not going get the payout that’s great. You’re not going to get paid time off.

PAUL SOLMAN: And Michael Mandel says it’s right there in the data.

MICHAEL MANDEL: On average, pay in fulfillment centers is about 30 percent higher than pay in brick-and-mortar retail in the same area. Not only that. Retail jobs tend to be part-time, maybe not paying benefits.

The fulfillment centers have a lot of full-time jobs, have the benefits. They seem to be better jobs, as far as I can figure out.

PAUL SOLMAN: D’Angelo Bryan, who’s been packing shipments at the Baltimore fulfillment center for a couple months now, even convinced his friends to apply.

D’ANGELO BRYAN, Amazon Employee: I got experience in just about a little bit of everything, and so far, I would definitely say Amazon is the best job that I have had so far.

PAUL SOLMAN: But let’s not romanticize here. The work is grueling.

D’ANGELO BRYAN: We’re packing really, really fast because we have shipments nonstop. The first couple of weeks, it was like, I don’t know how people do it. Being on your feet for 10 hours a shift, 44 hours a week, sometimes 50, you know, after those first two weeks, it’s like, whew.

PAUL SOLMAN: Now, warehouse work is dominated by men, while the retail economy is losing jobs that are mostly held by women. And fulfillment center jobs simply may not be feasible for laid-off brick-and-mortar workers for a host of reasons, among them, says Cohen:

MARK COHEN: These are folks who need flexible scheduling and are not able to commute 50 or 100 miles to an Amazon fulfillment center that’s open somewhere in the vicinity.

PAUL SOLMAN: But to Mandel, the net effect is positive, especially given America’s ever-widening inequality gap.

MICHAEL MANDEL: The rise of the fulfillment center jobs is having the effect of reducing inequality, because what you’re doing is you’re talking about raising the wages for people with a high school education by 30 percent. That’s significant.

PAUL SOLMAN: As automation takes over store jobs, though, won’t robots eventually displace the pickers and packers too?

Amazon already uses robots to move goods around. Not to worry, says Amazon’s Lynch: The company will simply keep growing and have to add jobs.

LAUREN LYNCH: Having robots in our fulfillment centers means that we can have more inventory, which means we need more associates to help us fulfill all that inventory, all those customer orders.

PAUL SOLMAN: But for how long will Amazon and others rely on humans to pick and pack?

And so we end with Cartman, a robot built to pick and stow items in a warehouse. It recently won a robotics prize sponsored by Amazon.

For the PBS NewsHour, this is economics correspondent Paul Solman.

HARI SREENIVASAN: Next week, Paul will look at how retailers both on- and off-line are responding to shifting consumer habits.

And on our Web site, the co-founder of eyeglass chain Warby Parker gives us his take on the transformation of retail. That’s at pbs.org/newshour.

[“Source-pbs”]